No, this is not an article about the Monk, ABC comedy-drama police procedural. Let’s get that out of the way, first and foremost. We’re talking actual monks, people, as in Tibetan Buddhism. What’s that have to do with TV, you ask?

The answer is a 2014 film by documentarian couple Tina Mascara and Guido Santi that tells the story of a man born into American fashion aristocracy, who forsakes all (well, most all) conveniences and dedicates his life to spiritual enlightenment. The subject of Monk With a Camera is Nicholas Vreeland, the grandson of the late Vogue editor Diana Vreeland and the son of former CIA officer and later U.S. Ambassador to Morocco Frederick Vreeland, who looks incredibly like an older and bald Steve Carrell.

Born abroad with a silver spoon, the younger Vreeland was a promising fashion photographer, having embarked on his career at the age of 15 with the help of grandma and Irving Penn, who is famous for his work for the likes of Issey Miyake and Clinique as well as his celebrity portraits in Diana Vreeland’s magazine.

Growing up, Vreeland lived in Germany, Italy and France before finally coming to the U.S. to attend the exclusive Groton School in Massachusetts. But there, he had little in common with his classmates as he did not share their culture, and his quest to find his own began. Still, famous friends such as Richard Gere, writer John Avedon and photographer Priscilla Rattazzi attest to Vreeland’s one-time jet-setting ways and his fashion sense. For example, he had a beautiful head of hair.

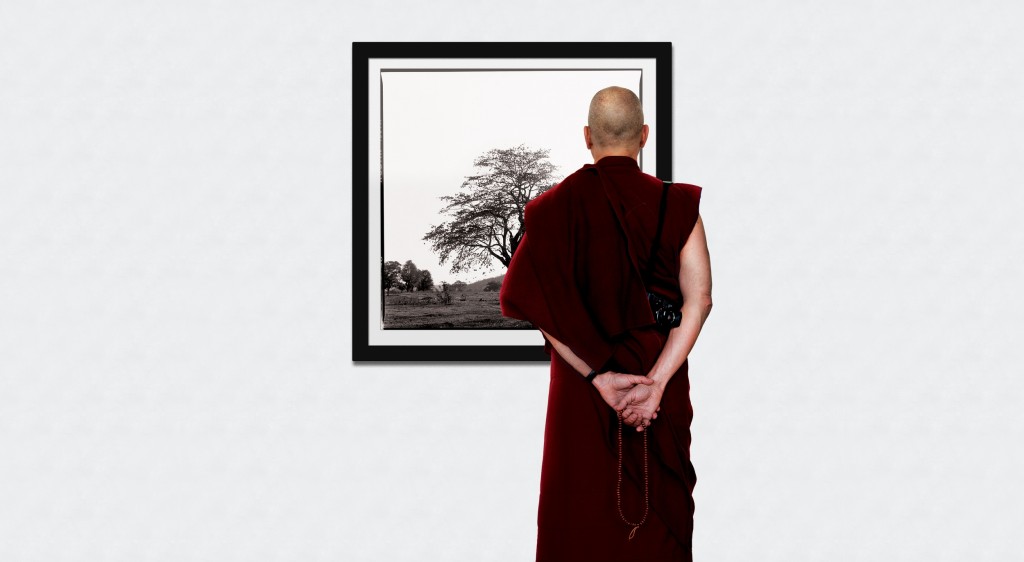

Today, he is a coif-less monk, wearing the traditional burgundy and gold robes, though his Birkenstock sandals are in impeccable shape with a shine like no other, a hold over from his upbringing as a proper Vreeland. But what makes the transformation truly ground breaking is that the Dalai Lama appoints Vreeland as the first Westerner in the history of Tibetan Buddhism to be the abbot of a monastery. And how it comes about is where the true story lies.

Vreeland uses his photography skills, which despite several decades of forsaking his occupation and lifestyle for his spiritual path, are still spot on as he tries to raise money to renovate the Rato Monastery. He first studied there in the 1980s after becoming enamored with Buddhism during his travels as a professional photographer and graduating from meditation to wanting to turn over his entire life to the pursuit of dharma. That’s where he met and studied under his good friend Khyongla Rinpoche, who has since “de-robed” and now ironically lives in a cozy Manhattan walkup.

Now, you might ask, isn’t taking artistic photos, subjects most of which Vreeland has relegated to trees, landscapes, monuments and people throughout the India countryside where Rato is located (oh, and in New York’s Central Park, one of the many incongruences of the documentary), contrary to a monk’s vow of poverty and celibacy? Yes, but no, which further captures the contradiction of the documentary. And that, one surmises, is exactly Mascara’s and Santi’s point. But Vreeland’s compositions are truly very good, after all, and he’s received permission from his teacher, Khyongla, and later His Holiness himself. So all’s well. It seems even Buddhist spiritual leaders know full well the power of branding and fundraising.

Of course, all of Vreeland’s high-powered friends and family, led by brother Alexander, the luxury fragrances and goods mogul who runs the company named after their grandmother, get in on the act. While no dollar amount is given, one can assume the auction brings in a pretty penny, not that building a monastery about 622 km, about 385 miles, southeast of Mumbai in remote Bangalore countryside must cost that much. Still, we learn from Nicholas that, whatever the necessary amount, donors dried up with The Great Recession, hence the need to hawk his skills.

While it all can seem a little self-serving and, well, odd, viewers are reminded that the objective is to build a better home for some 400 monks who administer to the local poor. And, as Mascara and Santi told the Los Angeles Times, they had to convince Nicholas Vreeland to even do the documentary in the first place, as he initially found the project to be in opposition to his spiritual practice.

But, in the end, good filmmaking, albeit somewhat barren but fittingly so for the subject, wins out. It’s about re-examining one’s belief system and priorities and realizing there is an alternative to all that we as Americans believe to be the way to live life.

Monk with a Camera is not an action-packed 90 minutes, that’s for certain, but it is an alternative to your Netflix consumption that provides a new perspective on society and spirituality. That said, it might truly resonate only with viewers residing in such areas as the New York’s Upper East Side or Los Angeles’ Westside, but it all seems worth it in the end to watch the Dalia Lama ham it up in a Long Beach hotel room.